Bang-Bang Satellite Controls

Something that’s very fascinating to me which I never learned about in school is bang-bang control design. So I bought and read some books to get a theoretical & quantitative background on the subject. But I still didn’t have much qualitative ‘intuition’ so that’s what this project is for. I didn’t achieve something specific in this project per se, as much as just mess around with some bang-bang controllers.

Bang-Bang Background

There are many control systems in which the actuators are binary — that is, either on or off. One example is many reaction control thrusters on rockets and spacecraft are controlled by an on/off isolation valve. Therefore your thruster can either be providing torque or not providing torque, and there isn’t any in-between.

It would seem initially that all of assumptions made with linear control theory break down and there’s nothing that us controls engineers can do about this, but luckily that is not the case.

An Easy* Solution: Pulse Width Modulation

A similar problem has already been solved in the field of electronics and circuits, and that is pulse width modulation. For example if we want to generate a 5V signal but our supply can only output either 0V or 10V, we can switch back and forth between 0V and 10V really fast. And provided we’re switching sufficiently quickly we can generate whatever voltage between 0 and 10 we want just by modifying the duty cycle of the switching.

We can apply this to our attitude control problem: the controller outputs a desired torque, and this can usually be mapped to a desired pulse width via some static gain. So then instead of a direct torque command, the thruster valves are simply commanded when to open and when to close. And as before, provided we switch back and forth fast enough between open and closed we can essentially perfectly match the non-bang-bang counterpart. Great!

Well it’s obviously not that simple…

For starters, we’re still succeptible to saturation. That is — if the controller wants more torque than the thrusters can provide when open 100% of the time, our performance is going to suffer pretty heavily. The way around this is to somehow increase the pulse height, so at 100% open, we can provide more torque. But this comes at a cost, which we’ll discuss soon.

The next problem we’ll run into is that hardware can’t respond arbitrarily fast! I know this firsthand from the valves work I did at SpaceX. Attitude control thrusters have a certain (nonzero) rise time, so we can’t actuate them arbitrarily fast. This means that we can’t access very low duty cycles, which creates a deadband. The problem with increasing the pulse height from the last paragraph, is that for a given thruster rise time, the deadband increases too.

So between the saturation and the deadband, our output will definitely not perfectly match the continuous-actuator counterpart. But that’s not the end of the world, we have tools to analyze stability margins, etc.

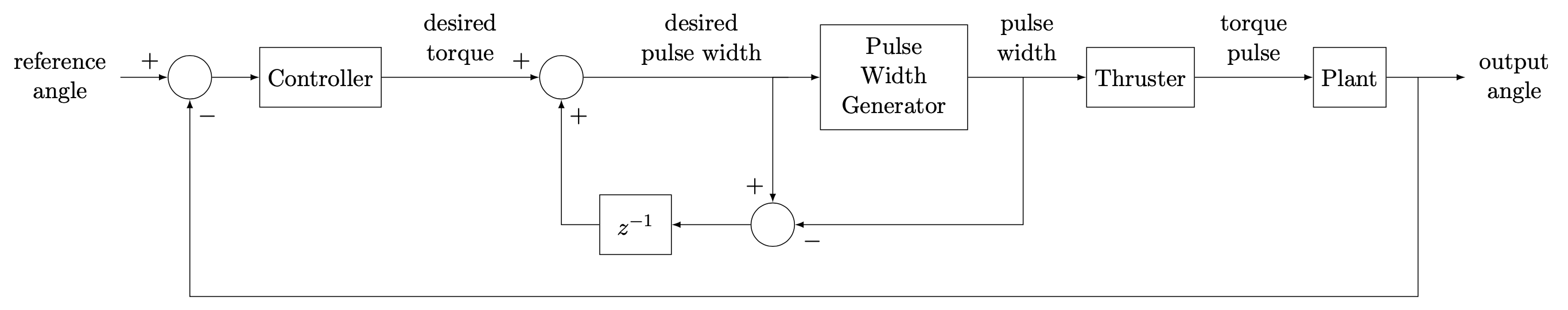

PWM + Accumulated Residuals

There are other clever ways of improving our performance with this nonlinear actuation system. One such clever way which I particularly like, is to keep a sort of running tally of pulse width errors, and add that error to the pulse width command at the next timestep. Obviously this won’t fully solve the problem because this method has inherent lag associated with it, but it still can significantly improve performance. Below is a block diagram showing how these “accumulated residuals” are handled in a system sense.

One cool thing about this is that linear controllers still apply. There are other ways to handle pulse widths which are not compatible with linear controllers, but with this method we have all of linear control theory at our disposal.

It’s also very possible to model all these nonlinearities as disturbances in the linear system sense, but I don’t have space to dive fully into that.

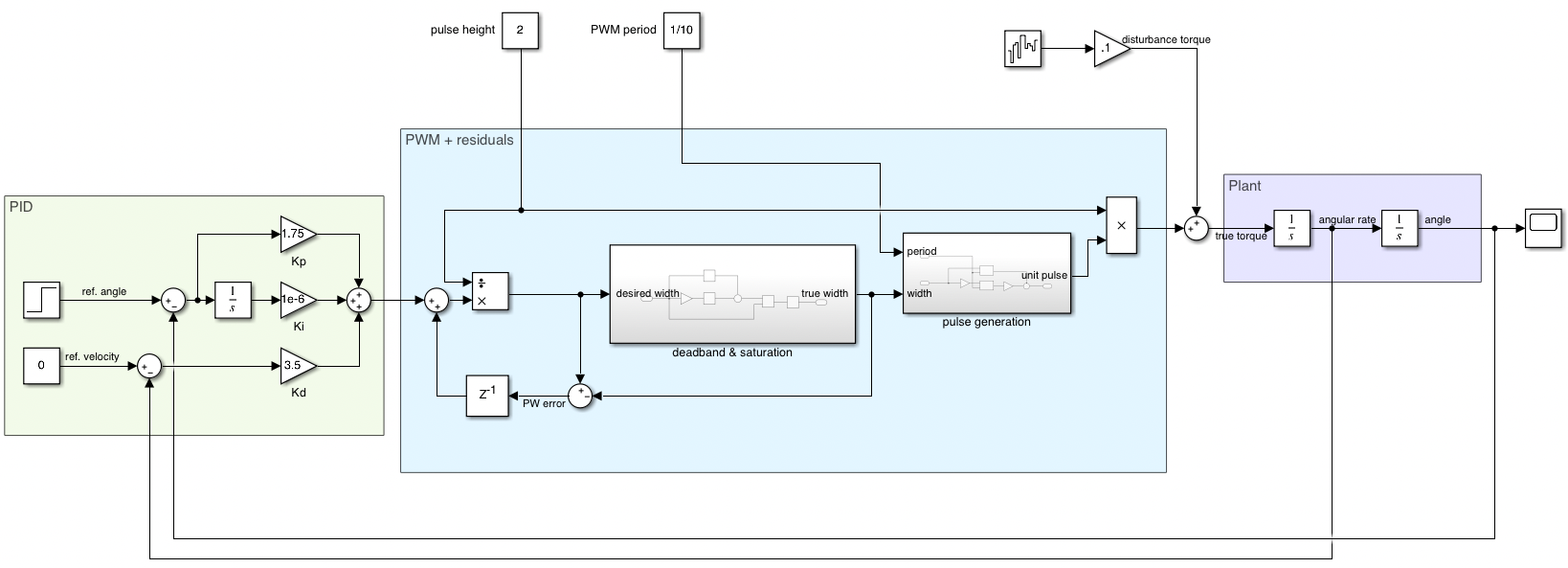

Implementation in Simulink

As a way to play around with this bang-bang control problem I created the below sim in Simulink. I chose my plant to be a super simply double integrator satellite system, since the control problem I’m interested in is satellite attitude control.

As you can see, I used a (linear) PID controller which outputs a torque command. This goes through a number of blocks as described above, and finally a bang-bang torque command it imparted onto the satellite.

Some Results

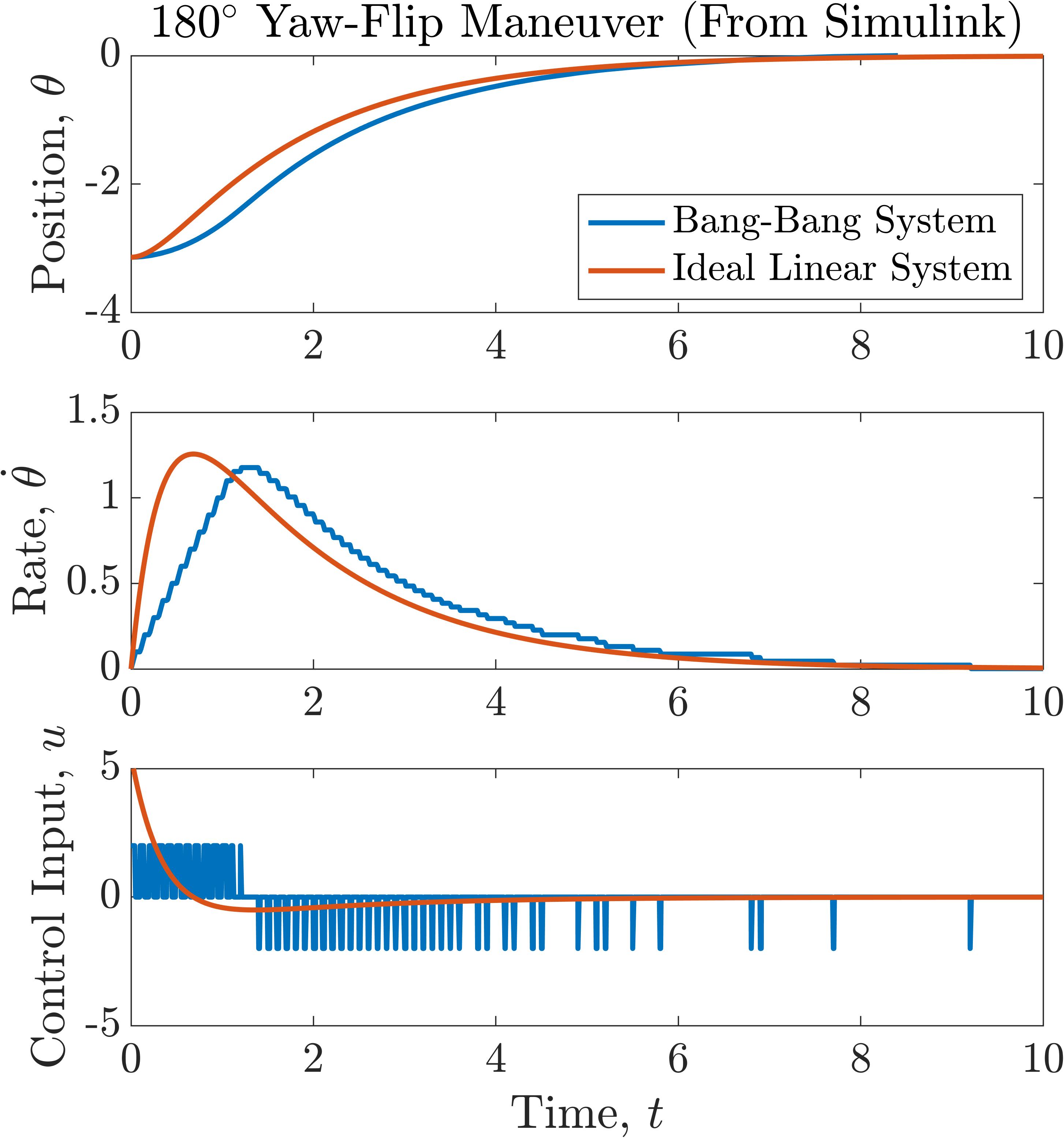

Most of my results at this point are pretty hand-wavey since I haven’t plugged in realistic numbers for anything. I’m just trying to get a qualitative sense of how a bang-bang controller affects performance. For example, the plots below are for a satellite performing a yaw-flip maneuver. This is when the satellite spins 180 degrees about its yaw axis. Most satellites in GEO perform this maneuver twice a year.

There are a few things to note from here. The bang-bang controller is saturating between 0 and ~1.5 seconds, asn the PID is commanding too high of a torque. The PID could be tuned to avoid this, or we can accept a little bit of saturation in exchange for faster responses in general. Due to this saturation, the bang-bang system lags behind the ideal system in its maneuver, but the two behave very similarly.

GUI From MATLAB (work in progress)

One of my future goals for this project is to make some kind of user interface where someone can play around with attitude reference, disturbances, pulse height, etc. in real-time. I haven’t gotten too far, but here’s a video I made of a satellite performing a the same yaw-flip maneuver as shown before in Simulink.